A Retrospective on 30 Days of Daily Blogging + Updates

Onwards

If you're reading this on Substack or over email, you probably thought I took the month off. But you would be wrong!

November was actually my most prolific month of blogging. Before November, I published 13 posts in total. I published 30 blog posts in November alone, over double what I had achieved over the course of the previous nine months.

Logistics

All posts are live and available on humaninvariant.com. You may have seen some posts already on MR and HN.

Across the next month, I will be posting select posts from the past 30 days to the Substack mirror and the mailing list. Others will be published to the Substack mirror without a post notification.

Retrospective

I published 28,427 words by posting every day over the course of November. Some topics I covered include:

- Third derivative work (building off of No One is Really Working)

- The negative externalities of agency-maxxing "you can just do things" posts

- Blame as a Service

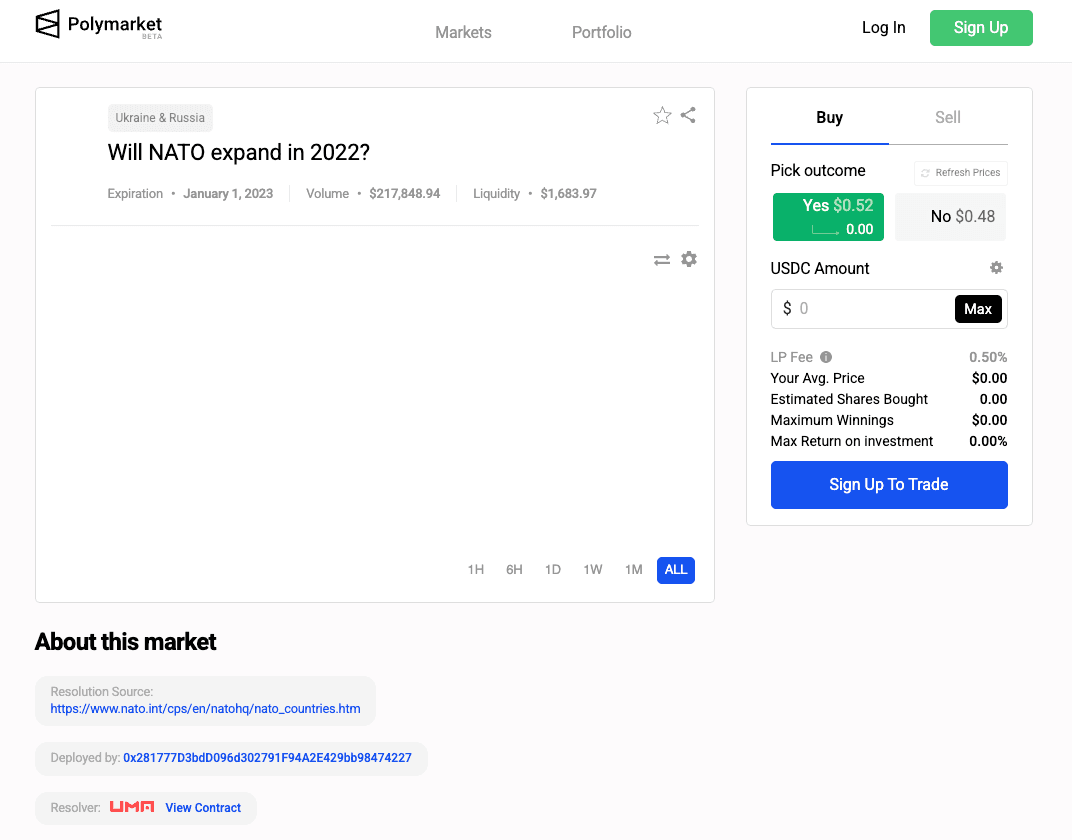

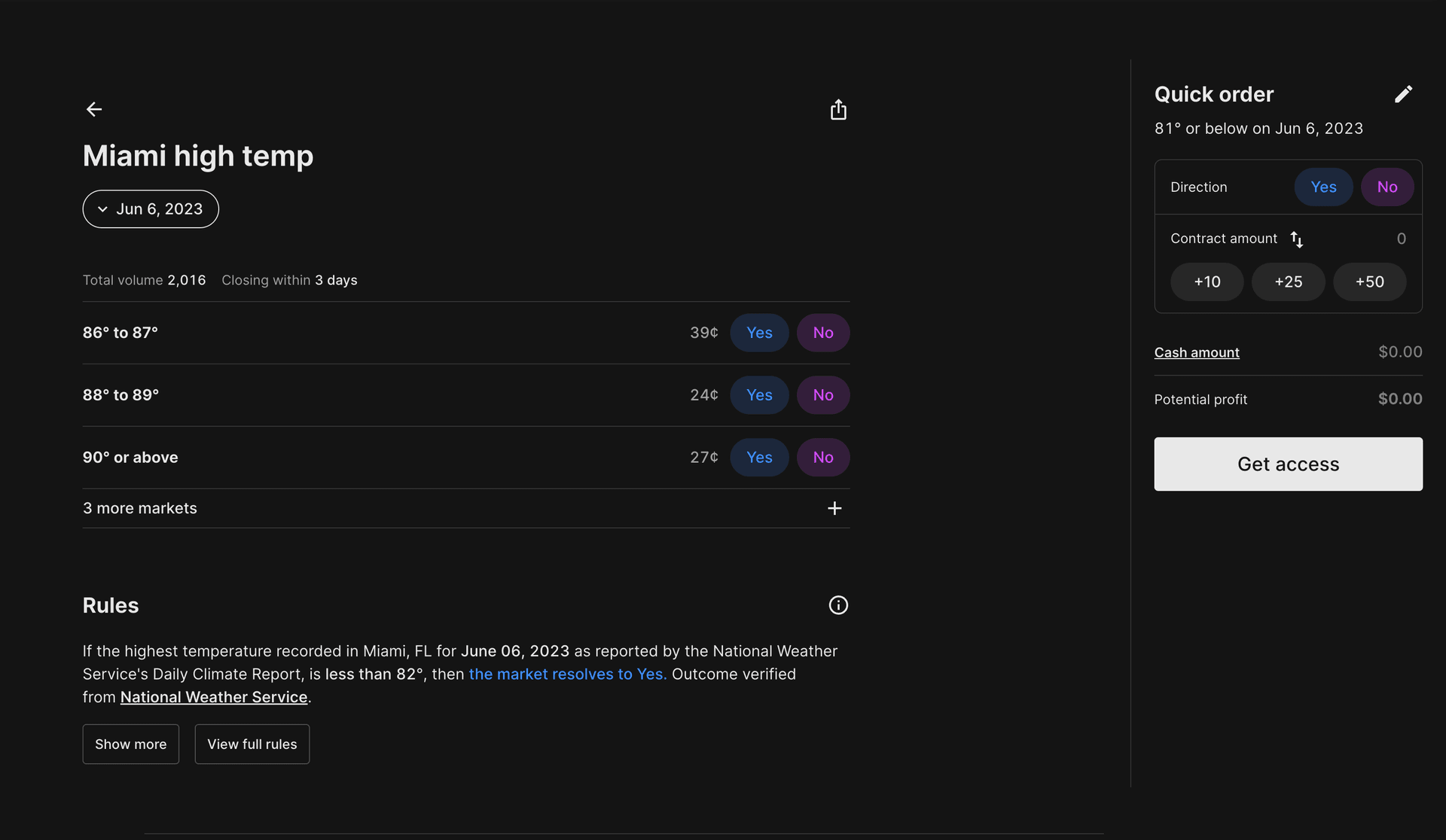

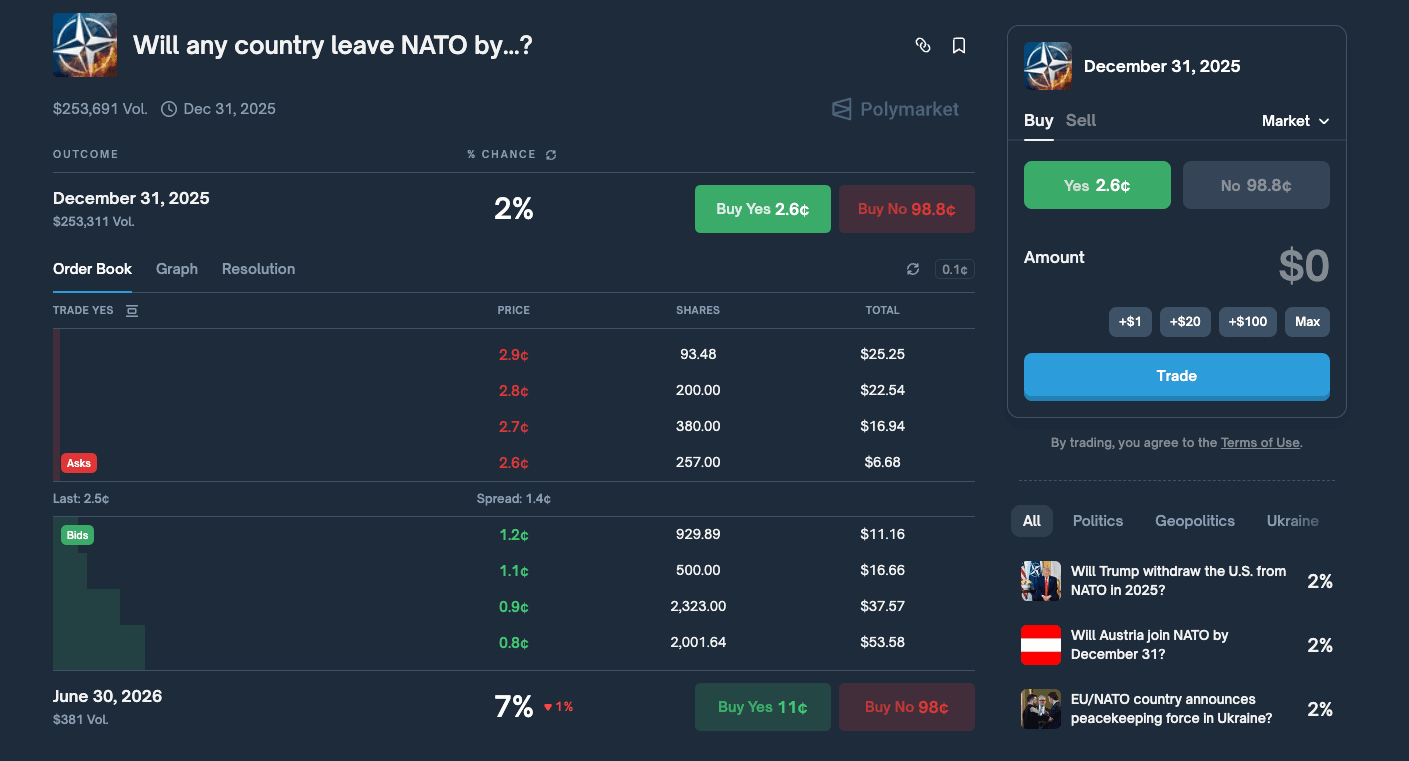

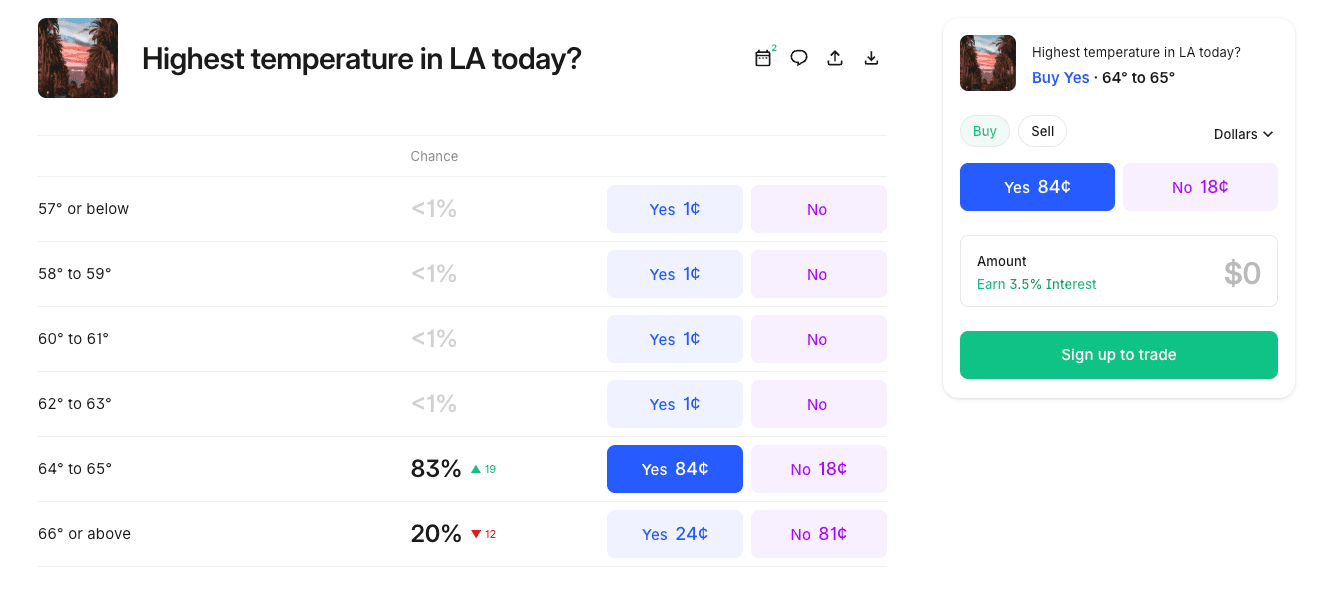

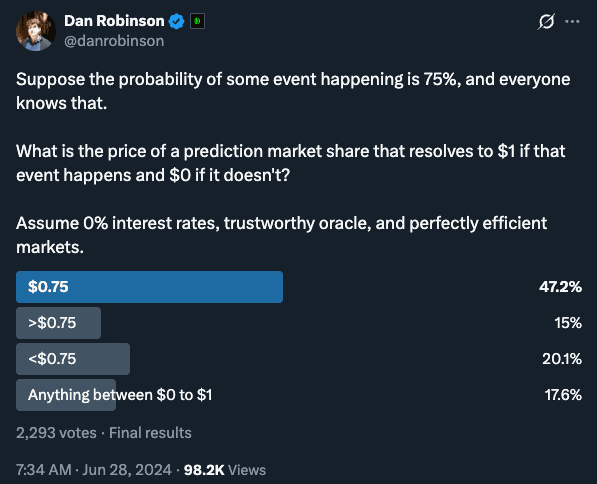

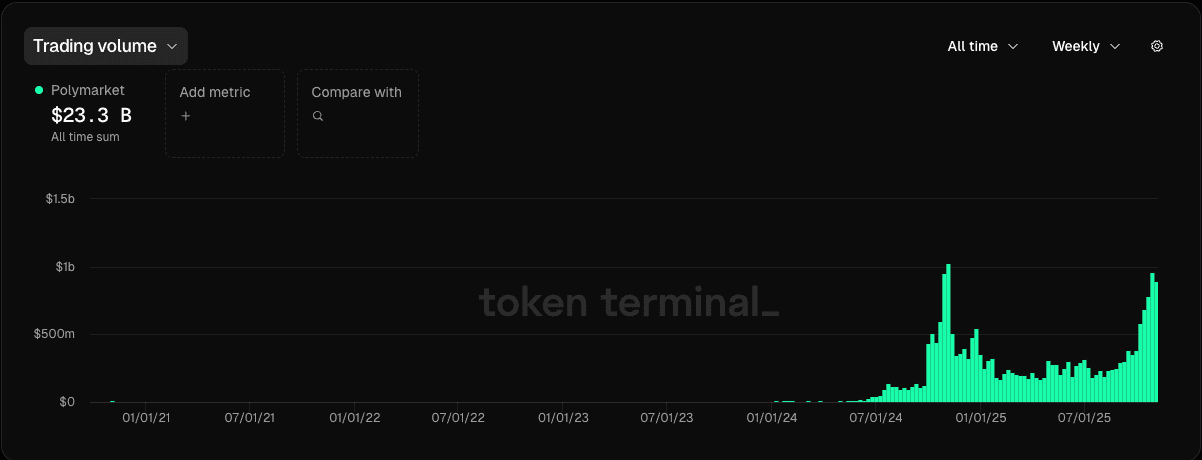

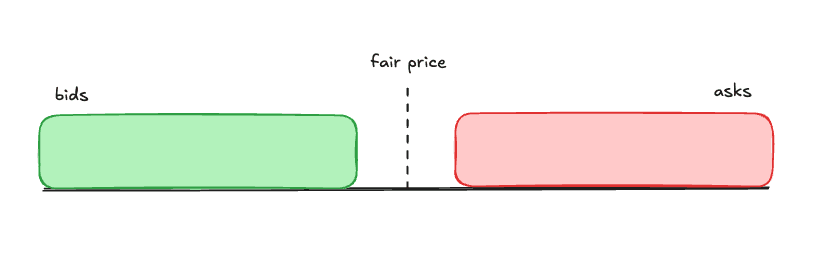

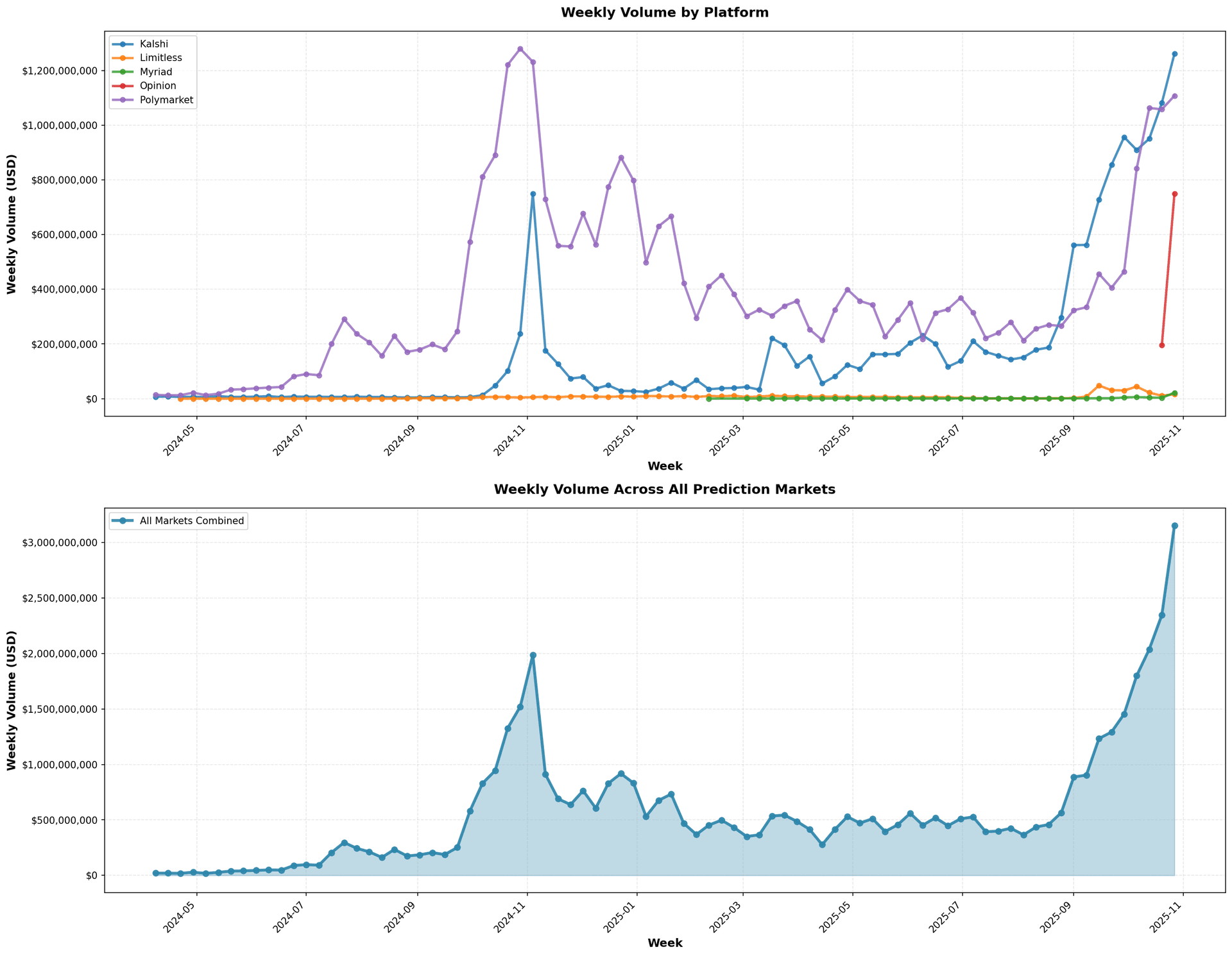

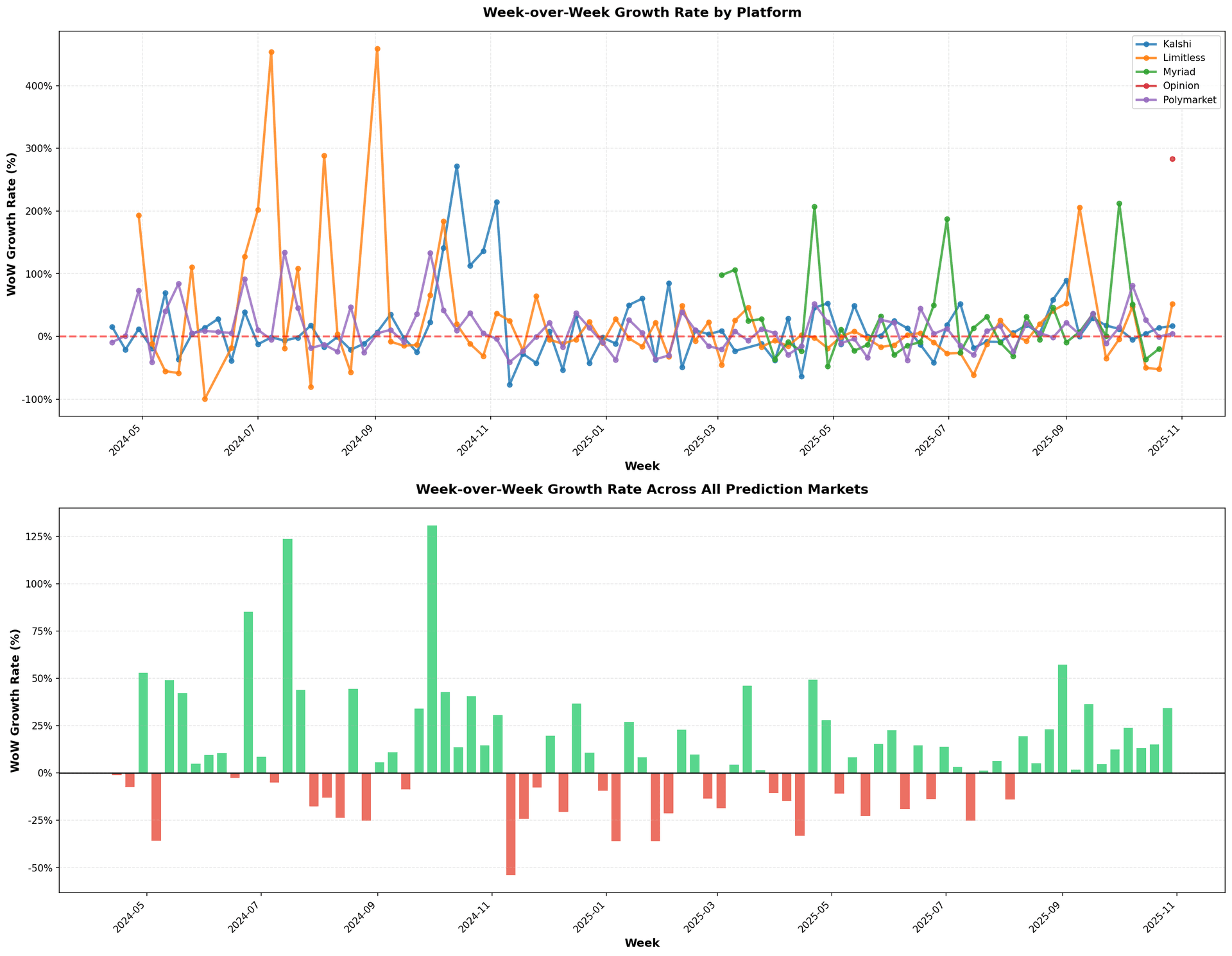

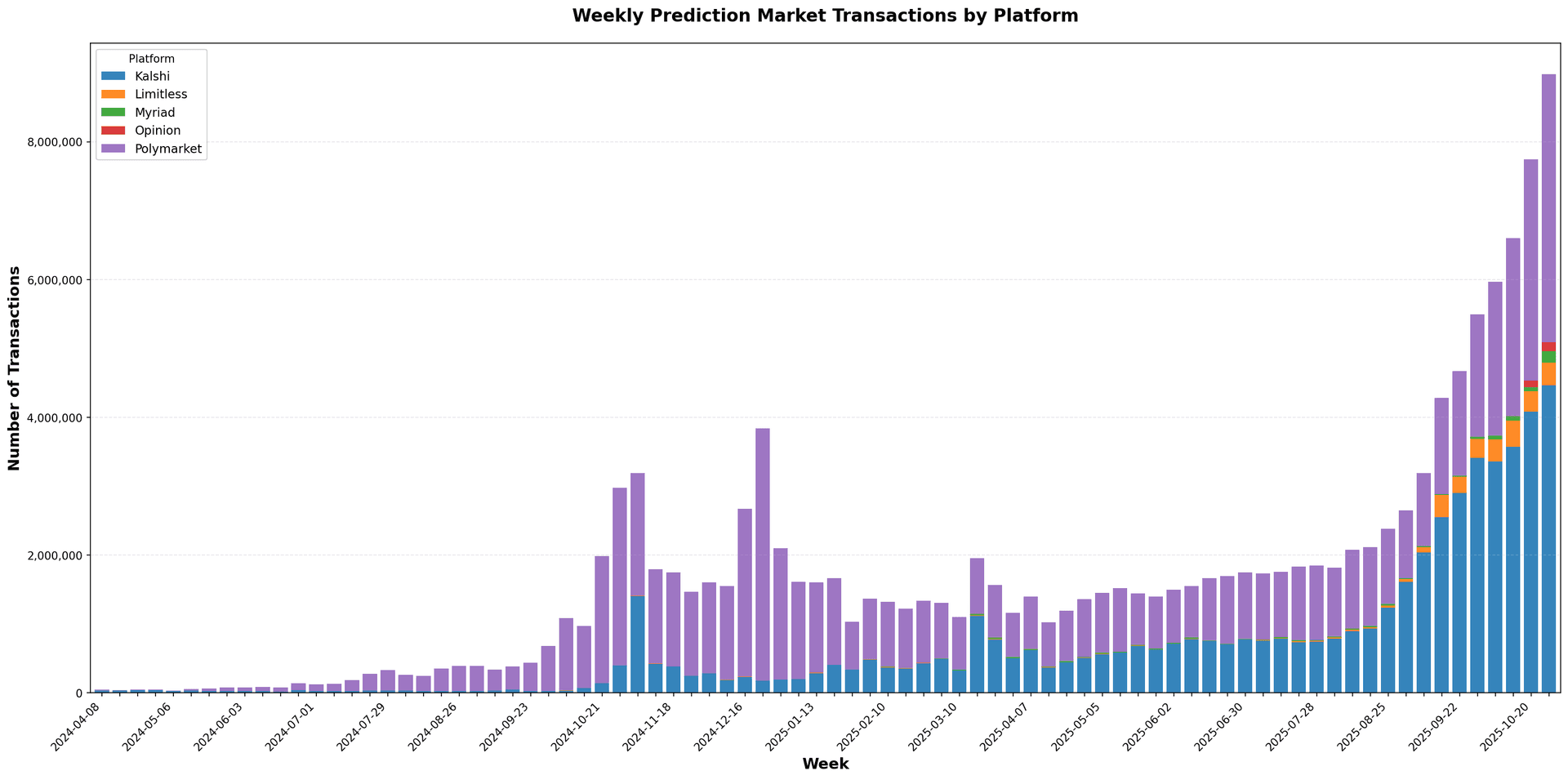

- Prediction markets

- the lowercase aesthetic

- Why are conversations and my productivity better late at night?

- The market microstructure of YouTube

- Observations from in person interactions with successful bloggers

- Understanding the scale of the internet

To be sure, not all posts I wrote during this stretch are good. Some days I really did not want to write, and likely would have quit without external pressure. But I learned just how good of a forcing function publishing a post every day is. It enabled me to explore more ideas than a typical month of one or two posts, and now I have many more ideas I'm excited to explore.

Many of these posts were specifically enabled by being in person and talking with other people I had never met before. I spent the month with people who have been thinking about prediction markets for years, including someone who ran internal prediction markets at Google in 2017 and an academic who was an early author of many prediction market papers.